Indu Banga

Panjab University, Chandigarh

Subscribing to the view that sovereignty for the Khalsa was conceived by Guru Gobind Singh himself, this essay postulates a close connection between the ideology of the Khalsa and their ability to subvert the Mughal state, withstand the Afghan invasions, and establish their own rule. In the new centers of power created by the Khalsa and later unified by Ranjit Singh, ideology appears to have influenced the conception of sovereignty, attitude towards political rivals, patronage of different faiths, administration of justice, and participation of people from diverse social backgrounds in the army and administration. Yet, all the components of the Khalsa ideology were not equally operative through this period, and there was evidence also of tension between ideology and praxis.

___________________________________________________________

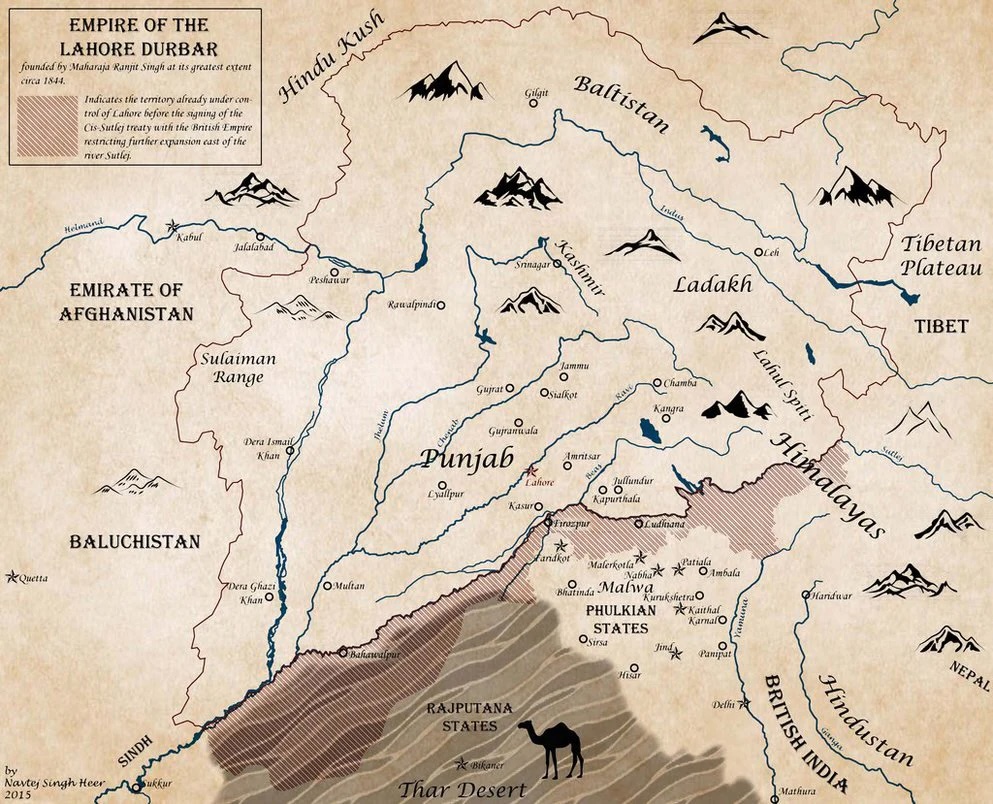

The decline of the Mughal empire was accompanied by the rise of a number of regional polities. About half of nearly 120 small centers of power in the Punjab region had been created by the Khalsa of Guru Gobind Singh during the late eighteenth century. Emerging as a political power about the same time, the East India Company became paramount in a large part of the subcontinent half a century later. The only other independent state in India at that time was that of Ranjit Singh. By the early 1820s, he had unified the new foci of power in the northwestern region into the powerful state of Lahore. His sovereignty was symbolized by the coins which bore the same inscriptions as the seal and coins of 1710, deriving authority from Guru Nanak and Guru Gobind Singh.

Historians have conceptualized this period of rapid transition in the northwest in conflicting terms. They either see no relevance of the religious ideology of the Sikhs for their political order, or see it as a ‘theocracy.’ In some works ‘the spirit of equality’ and ‘direct democracy’ are seen as the governing principles, leading to the ‘rule of the collecti-vity’ and the ‘joint ownership’ of land by the whole Sikh nation. Logically, then, the period of Ranjit Singh is treated as ‘a debris of the marvelous democracy of the earlier period.’ In other works, the late eighteenth century Sikh rule is seen as an ‘oligarchy,’ or at best a ‘confederation.’ Ranjit Singh’s state is seen as a ‘military monarchy’ restoring order, or a political system subject to a ‘theocratic commonwealth.’1

This essay proceeds on the assumption that the common thread in the history of the Sikhs after the institution of the Khalsa by Guru Gobind Singh in 1699 could be found in the Khalsa ideology which itself can be partially but essentially traced to the early Sikh tradition. The close connection between the Khalsa ideology and the political process had a close bearing also on the structure and functioning of the polity that came into existence during the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth century. The term Raj Khalsa here denotes the acquisition and exercise of power together with its ideological underpinnings.

The Ideology of the Khalsa

The ideology that motivated the Khalsa of Guru Gobind Singh was a combination of the principles of equality, social commitment, justice, and freedom of conscience enunciated by Guru Nanak, and upheld at the cost of their lives by Guru Arjan and Guru Tegh Bahadur. Building on this inheritance, the tenth Guru looked upon the sword as a legitimate source of protective power. The institution of the Khalsa and the baptism of the double-edged sword (khanda di pahul) reinforced the principle of equal-ity, extending it to the political sphere. The differences of birth were obliterated on joining the Khalsa who were to keep their hair unshorn, wear turbans, wield weapons, ride horses and use the suffix ‘Singh.’2 The traditional attributes of a sage were combined with the essential features of a warrior. The Khalsa were inspired to consecrate their lives to the cause of righteousness, with sacrifice built into the ideal.

The desirable conduct for the Khalsa men and women came to be compiled in manuals of beliefs and conduct to serve as the ideal way of life (rahit) for the Khalsa in the changing socio-political contexts. Among other things, the contemporary manuals spell out the negative and positive injunctions for a warlike people who remained committed to their faith and observances, revered arms, fought against injustice and oppression, and upheld certain ethical values in their personal and familial life, interpersonal relations, and even in warfare.3 The Nasihatnama, a manual of instructions attributed to Bhai Nandlal, and placed recently in the period between the institution of the Khalsa and the death of Guru Gobind Singh, ends with a prophecy of sovereignty for the Khalsa: ‘raj karega Khalsa.’ Evidently, ‘sovereignty for the Khalsa was conceived by Guru Gobind Singh’ himself.4

A day before his passing away at Nanderh, in October 1708, Guru Gobind Singh told his followers that henceforth they should consider the Guru dwelling in themselves, and for inspiration they should refer to the Bani. His court poet Sainapat identifies the Sangat with the Guru, making the collective body of the Khalsa authoritative for the individual member.5 This marked the beginning of a new phase in the history of the Sikh movement. In place of the personal Guru, the Sikhs were to go to the Guru Granth Sahib for guidance and to the collectivity of the Gurus’ followers for decision-making. This proclamation gradually crystallized into the doctrines of Guru – Granth and Guru Panth.

The First Bid for Sovereignty, 1708-16

Shortly before his death at Nanderh, Guru Gobind Singh commissioned a newly initiated Singh, called Banda, who was an aggressive Vaishnavite renunciant earlier, to lead the Khalsa to dislodge the unjust and oppressive rulers from power.6 By then Guru Gobind Singh had corresponded and interacted with two Mughal emperors, and spent over a year in the vicinity of the imperial camp with nothing tangible coming out of the Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah’s assurances with regard to Guru Gobind Singh’s return to Anandpur.7 It seemed futile to expect justice from the Mughal emperor. In consonance with his belief in the legitimacy of the use of physical force for a righteous cause, Guru Gobind Singh commissioned Banda to lead the Khalsa in a bid for sovereignty.

Armed by the Guru’s orders (hukamnamas) for his followers, and accompanied by about a score of the Khalsa, Banda Singh set out for the North. A sufficiently large number of the Khalsa had gathered round him in a year. Before the end of 1709, he opened his attack on Samana in the sarkar of Sirhind, humbled its Mughal administrator and plundered the town. More Singhs joined the venture and more strongholds of the state fell to them. There were spontaneous uprisings of the Khalsa at different places in the province of Lahore.8 After the defeat and death of Wazir Khan, the faujdar of Sirhind in May 1710, Banda Singh occupied the plains between the rivers Sutlej and Jamuna and supplanted the Mughal administration with that of the Khalsa. A coin struck after the fall of Sirhind proclaimed the sovereignty of the Khalsa. Despite mounting pressure from the Mughal authorities, the coins struck in 1711 and 1712,9 with ‘regnal years’ marked on them, indicate the seriousness with which the Khalsa took their sovereignty. The inscription on the seal used for orders in 1710 reinforced the idea of sovereignty.10 Apart from appointing his own revenue collectors and garrison commanders in the conquered territories, Banda Singh extracted tribute from the hill chiefs who were subject to the Mughal emperor and paying tribute him.

The Mughal emperors Bahadur Shah and Farrukh Siyar had to pay close personal attention to the ‘rebels’ for several years before Abdus Samad Khan, the Lahore governor, laid siege to the fortress of Gurdas Nangal in 1715. After severe hardship for eight months Banda Singh and his seven hundred plus companions surrendered in December 1715. They were taken to Delhi, given the usual option of accepting Islam, and on their refusal, tortured and executed in 1716.

The rise of the Khalsa under Banda Singh’s leadership exemplified that an inspiring ideology could compensate for the initial lack of political organization and military apparatus. The Khalsa looked upon themselves as the agents of the tenth Guru fighting for creating a just political order. In less than three years, the lowly peasants and artisans from the countryside were elevated to the ruling position. Banda’s armies extended protection to the ordinary subjects of the erstwhile Mughal state and even provided opportunities to them for participation in the new order. In his hukmnama Banda claims to have established ‘satjug,’ the rule of true dharma.11 Sainapat refers to the new order as ‘Ram-Raj’ which banished oppression, reinstated justice, and assured freedom of conscience.12 The dignified bearing and steadfastness of Banda and his companions in the face of death made them martyrs in the cause of righteousness.13

Banda’s hukmnama refer to ‘Sachcha Sahib’ and strict observance of the rahit. However, it underscores preference for vegetarianism, and ‘Fateh Darshan’ in place of ‘Vaheguru Ji Ka Khalsa Vaheguru Ji Ki Fateh.’ According to Ratan Singh Bhangu, the historian of the Khalsa, Banda did not seem inclined to share power with the staunch associates of Guru Gobind Singh (tat-Khalsa) who maintained that Banda had only been assigned a ‘service’ and that the tenth Guru had bestowed sovereignty upon the collectivity of his followers (Panth). Guru Gobind Singh was believed to have prophesied ‘rulership for each saddle’ (hanne hanne hon mir). The Khalsa charged Banda with deviation from the established Khalsa practices by adopting the salutation ‘Fateh Darshan,’ by insisting on vegetarianism, and by preferring red dress of the Bairagis to the traditional blue dress of the Khalsa. His observance of ritual purities, due presumably to his Bairagi background, militated against the casteless order (sarbangi reet) created by the baptism of the double-edged sword. The old Khalsa dissociated from Banda and went to Amritsar.14

Within fifty years of Banda’s execution, the Khalsa rule was formally heralded in 1765. The ideal of ‘raj karega Khalsa’ had continued to inspire the followers of Guru Gobind Singh through this period. Despite the repressive measures of the Mughals and the Afghans, there was a steady increase in the striking power. Their ideology enabled them to evolve new ways of cohesion and new forms of organization as an alternative to the framework of power under the Mughal empire.

Recovery of the Khalsa

Independently of Banda and even before the fall of Sirhind, the Khalsa had established control over Ramdaspur (Amritsar), which became their rallying center after 1716. The news-writers of the decade up to 1726, when Abdul Samad Khan was transferred from Lahore to Multan, refer to the stray attempt of the Khalsa to paralyse Mughal administration. After an initial effort at vigorous repression, Zakariya Khan, the new governor of Lahore (1726-1745), tried conciliation and persuaded the emperor to induct the Khalsa into the imperial framework. In 1733, their leader was offered a revenue assignment (jagir) near Amritsar, a robe of honor and the title of ‘Nawab.’ Initially the Khalsa were not inclined to accept the offer because of their belief that ‘the Panth was sovereign’ and ‘Nawabi’ signified subordination. After much deliberation, however, they decided to gain reprieve from a constant state of warfare. They passed on the robe and the title to Kapur Singh who was known for his service to the Khalsa.15 Kapur Singh figures later as an important leader, generally remembered as Nawab Kapur Singh.

During this peaceful interlude many new persons took the baptism of the double-edged sword and joined the Singh warriors. Kapur Singh is said to have organized them into five units (deras). They had a common kitchen, treasury, stores, arsenal, and granary for horses. Each dera had its own leader and standards (nishan). Two of these leaders were Jats, two Khatris (one Trehan and the other Bhalla, descendants respectively of the second and fourth Guru), and one was an outcaste Singh called Bir Singh Rangrehta.16 It may be assumed that all the five leaders were men of exceptional qualities and dedication. The choice of a Rangrehta (scavenger or as a Chuhra by caste) for leadership symbolized a veritable social revolution. In due course, the leaders of the Khalsa would emerge from amongst the carpenters, distillers, and ordinary cultivators.

The town of Ramdaspur (Amritsar) appears to have played an important role in the remarkable recovery of the Khalsa since the fall of Banda. Bhai Mani Singh, an associate of Guru Gobind Singh, is believed to have been given charge of the religious center by the Guru himself.17Pilgrimage to Amritsar on Baisakhi and Diwali was revived, and the Khalsa began to visit the place as a matter of routine. By 1710, ‘lakh upon lakh of these people’ were reported to be collecting there on the Baisakhi day, to ‘engage themselves in dance, sport and bathing.’18 Therefore, Zakaryja Khan also thought of giving jagir to the Khalsa around Amritsar. The renewed activity of the restive Khalsa signaled the end of the truce and Zakariya Khan resumed the jagir. In an effort to demoralize the Khalsa, he imposed controls over Amritsar and executed the venerable Bhai Mani Singh who is said to have deliberately courted a painful death.19

Instead of acting as a deterrent, the martyrdom of Bhai Mani Singh spurred the Khalsa into greater action. They intensified their military activity, extending it to the sarkar of Sirhind. In 1739 they plundered the rear of the army of Nadir Shah who was returning from Delhi with a huge booty and a formal treaty by which the Mughal emperor had ceded the trans-Indus territories to him, together with the revenues of four parganas of the Lahore province. The daring of the Khalsa was noticed by Nadir Shah, and on his learning that their ‘homes are in their saddles,’ he is believed to have warned Zakariya Khan against their potential to capture power.20

Till his death in 1745, Zakariya Khan tried his utmost to crush the Khalsa, even taking over the town of Ramdaspur and desecrating the Harmandir. In the backdrop of tussle for power after his death, the Khalsa were able to increase their numbers and intensify their operations, plundering even Lahore. In 1746, about four to seven thousand of the Khalsa were killed in a persistent action remembered as a carnage (ghallughara). The civil war between Zakariya Khan’s sons in 1747 enabled the Khalsa to increase their resources. In 1748, the number of their bands (jathas) under the old and new leaders was reported to be in scores.21 They decided to unite their forces under a single command whenever necessary for more effective defense and offense. The construction of the mud-fortress of Ram Rauni close to Amritsar in the same year may be seen as a prelude to territorial occupation.

Contest for Sovereignty

After the victory of the Mughal armies against Ahmad Shah Abdali in 1748, Muin-ul-Mulk, popularly known as Mir Mannu, became the governor of Lahore and pursued a policy of ruthless repression combined with conciliation with regard to the Khalsa. When Ahmad Shah Abdali invaded Lahore in 1752, Muin-ul-Mulk received no help from Delhi and felt obliged to submit to him, also obliging the Mughal emperor Ahmad Shah to subsequently cede the province of Lahore to Abdali. On behalf of his new master Muin-ul-Mulk continued, though without much success, with repressive measures against the Khalsa until his death in 1753. Meanwhile, the Khalsa had occupied pockets of territory in the upper doabs. The earliest available document pointing to the establishment of an individual Singh’s rule goes back to the year 1752. In this order of 17 April Hakumat Singh is addressing the present and future ‘amils and zamindars of qasba Kahnuwan’ and referring to the ‘rule of the emperors’ as the ‘old regime.’ He would issue another such order on 17 January 1755, using the seal of 1752. Jai Singh Kanhiya’s seal bears the date 1750.22 Thus, it is evident that the leaders of the Khalsa had begun to occupy territory and to issue orders in their own name before the formal end of Mughal rule in the Punjab in 1752. After Mir Mannu’s death there was no stable governorship at Lahore for four years. Some of the well-known Khalsa leaders established their influence in some specific territories, like Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, Hari Singh Bhangi, Charhat Singh Sukarchakia, Gujjar Singh Bhangi, Jassa Singh Ramgarhia, Baghel Singh Karorasinghia and Khushal Singh Faizullapuria, a nephew of Kapur Singh.

In 1757, Ahmad Shah Abdali obliged the Mughal emperor to cede the sarkar of Sirhind to him, and appointed his own son Taimur as the governor of Lahore. After Abdali’s return to Kabul in 1757, the Khalsa overpowered his son. The Marathas intervened on behalf of the Mughal emperor and occupied the Punjab up to the river Indus. Ahmad Shah Abdali decided to settle his score with the Marathas. He stayed in India in 1759-61 and gave a crushing defeat to the Marathas. During this phase the Khalsa are reported to have occupied territories on a much larger scale.23 Within months of the battle of Panipat in January 1761, they could oust the appointees of Ahmad Shah. In February 1762 he surprised them at a place called Kup near Malerkotla. The Afghans surrounded their camp, wounded and killed several leaders and warriors, and massacred thousands of women and children, their estimated numbers ranging from 10,000 to 30,000. After this carnage, called vaddha ghallughara in Sikh history, Abdali attacked Amritsar and blew up the Harmandir with gunpowder.

Apparently, the military strength of the Khalsa had increased manifold since the early 1730s. Commenting on the Great Carnage, a contemporary observer, Tahmas Khan, reports that ‘nearly one and a half lakh Sikhs, horse and foot,’ were present at this time.24 By now they were organized into larger units. Bhangu gives the names of eighteen units, called misls. As regards their social composition, the Jats were preponderant, but to the two deras led by the Khatris in the thirties had been added the misls of the Bedi and Sodhi descendants of Guru Nanak and Guru Ram Das who joined the Khalsa in the 1750s. The leader of the Ahluwalia misl came from a family of Kalals (distillers), and the Ramgarhia misl was led by a Tarkhan (carpenter) by birth. Compared to one dera led by a Rangrehta (scavenger by caste) in the 1730s, now two units were named after the outcaste Rangrehtas and Ramdasias (the Chamar converts).25 It seems that the casteless order (sarbangi reet) which was in evidence in the 1730s, had come to stay. Leadership remained open to merit irrespective of one’s social background.

It is not surprising that the Khalsa were able to rally within months of the Great Carnage. They fought engagements with Ahmad Shah’s forces, recovered control of Amritsar and defeated his nominees. No one dared ‘obstruct’ or ‘oppose’ this ‘sect of the Guru’–reported the news-writer from Delhi in March-April 1763.26 In 1764 they attacked Sirhind, killed its Afghan administrator along with 10,000 horsemen, sacked the town, and began occupying territories in the plains of Sirhind from the Sutlej to the Jamuna.27 Tradition describes how the Khalsa dispersed as soon as the battle was won, and how, riding day and night, each horseman would throw his belt and scabbard, his articles of dress and accoutrement, until he was almost naked, into successive villages to mark them as his.28

In 1764 the victor of Panipat suffered perhaps the worst defeat of his career. According to another news-report from Delhi, after a humiliating engagement with the Khalsa near the Chenab, he had to save himself by ‘putting his own horse into the river,’ and after crossing the river Jhelum his troops ‘fled pellmell, like an army without defense or transport.’ In this engagement the Khalsa were reported to have ‘more than one lakh horse and foot, with many well-mounted horsemen.’29 Thereafter, they were ‘treated with much awe by the Afghans.’30 Qazi Nur Muhammad, who accompanied Ahmad Shah later in the year, was constrained to admit that the Afghans had lost the entire country from Sirhind to the Derajat; it was now being enjoyed by the Singhs ‘without fear from anyone.’31

All through the political struggle of the Khalsa, the Harmandir continued to be their nerve-centre. During their most intense conflict with the Afghans in the early 1760s, the Khalsa were reported to be repairing frequently to ‘the Chak Guru’ (Amritsar) for bathing (ishnan), ‘division and distribution of the country,’ and ‘deliberation and consultation’ before fanning out for warfare and territorial occupation.32 Their confidence appears to have percolated down to the peaceful followers of the Gurus. For the Diwali of 1763 ‘a very large crowd’ was reported to have gathered at the shrine and the construction of houses in the vicinity was also underway.33 Qazi Nur Muhammad sees a connection between the faith of the Khalsa and their exceptional bravery, heroism and ethics. Ahmad Shah too seemed to be aware of the importance of the Harmandir for the Khalsa, and tried for the last time ‘to destroy the Chak as well as its worshippers.’ Nur Muhammad goes on to describe how just thirty ‘Sikhs’ who stayed back to ‘sacrifice their lives for the Guru, engaged 30,000 Afghans in battle and courted death.34 Their leader, as Bhangu narrates, was Nihang Gurbakhsh Singh who deliberately courted martyrdom with over a score of his companions.35

Ahmad Shah’s increasing ineffectiveness against the Khalsa was not lost on the news-writer. When the Shah decided to go back in March 1765 he was reported to be unable to ‘chastise’ them or to establish any posts (thanas) of his own.36 The Khalsa were the de facto rulers of the Punjab before they struck the coin at Lahore in 1765. Three leaders— Sobha Singh, Gujjar Singh and Lehna Singh—ousted the Afghan governor from Lahore, occupied the city and partitioned it amongst themselves. They formally proclaimed Khalsa rule by issuing a coin bearing the following inscription:

Deg-o tegh-o fateh-o nusrat-i bedirang,

Yaft az Nanak Guru Gobind Singh.

This was the inscription used by Banda on his seal, acknowledging on behalf of Guru Gobind Singh the gift of ‘bounty, power and instantaneous victory’ received from Guru Nanak. The Khalsa thus succeeded in regaining the state lost by Banda in 1715. Another coin with a similar import was issued later from the mint at Amritsar, using the same inscription as on the coin of Banda’s time:

Sikka zadd bar har do ‘alam, tegh-i Nanak wahib ast,

Fateh-i Gobind Singh, Shah-i Shahan, fazl-i Sachcha Sahib ast.

The sword of Nanak was seen as the bestower (of sovereignty) in the two worlds; the victory of the Khalsa of Guru Gobind Singh was due to the grace of God, the True King.37 Marking the declaration of the sovereignty of the Khalsa, the Nanak Shahi coins remained current in the territories of the largest number of the Khalsa rulers.38

Alternative Organization and Framework

To account for the success of the Khalsa a number of factors have been, and can be, invoked: the increasing numbers and resources, guerilla tactics, and competent leadership of the Khalsa; factions at the Mughal court; and the declining support of the jagirdars, autonomous chieftains, intermediary zamindars, religious grantees, and the trading communities for the governors of the province. However, center-stage in any explanatory scheme must be given to the ideology of the Khalsa that enabled them not only to sustain their struggle but also to evolve a new framework of action as an alternative to the administrative framework of the Mughal empire which had provided the starting base for the other aspirants for power during the eighteenth century.39

Qazi Nur Muhammad, who compiled the Jangnama in 1765, has an inkling of the relevance of the faith of the Khalsa for their success. He marvels at the exceptional proficiency of the Khalsa in the handling of traditional weapons, and asserts that ‘no one is more proficient than them’ in the art of using muskets while galloping. ‘To the right and to the left and also in the front and towards the back, they fire a hundred muskets in this manner.’40 They are said to have integrated this ‘art’ well with their ‘manner of combat’:

If their armies take to flight, do not take it as an actual defeat because this is only a battle tactic of theirs. Beware, beware of them again, because, this tactic of theirs is aimed at scattering the enemy in the excitement of pursuit (…) Then they turn back to face their pursuers and set fire to even water.

Qazi Nur Muhammad then refers to the ethics which distinguished the Khalsa from others:

At no time do they kill one who is not a man (namard). Nor would they obstruct the passage of a fugitive. They do not plunder the wealth and ornaments of a woman, be she a well-to-do lady or a maid-servant. There is no adultery among the Sikhs, nor are these people given to thieving.

He goes on to suggest some kind of connection between ‘the conduct of the Sikhs’ and their religion:

The ways and practices of these [people] are derived from Nanak who showed to the Sikhs a separate path. His [last] successor was Gobind Singh, from whom they received the title ‘Singh.’ They are not from amongst the Hindus. These rebels have a distinct religion of their own.41

The essential injunctions regarding beliefs, conduct and warfare embedded in the Khalsa ideology appear to have been internalized by the Khalsa much before they actually declared the establishment of sovereign rule in 1765. Significantly, Guru Gobind Singh was believed to have regarded the acquisition of fire arms ‘in plenty’ as a necessary condition for the realization of the prophecy that the Khalsa shall rule ‘everywhere.’42 The collective functioning of the Khalsa was guided by the doctrines of Guru Panth and Guru Granth that crystallized shortly after the death of Guru Gobind Singh. The cohesive devices evolved in the course of political struggle came to be known as the Gurmata, Sarbat-Khalsa, and the Dal-Khalsa.

Literally, a resolution passed in the presence of the Guru, the Gurmata denoted a decision taken with common consent in a council of war or a gathering (diwan). In a state of warfare a collective decision, often called simply the mata, did not necessarily have to be taken in the presence of the Guru Granth Sahib. The voluntary gatherings of Singhs – generally at Amritsar on the occasions of the Baisakhi and the Diwali – came to be known as the Sarbat-Khalsa. In principle, everyone present there had the right to participate in deliberations that had a bearing on the general interests of the Khalsa. Their decisions were considered morally binding even on those who were not present. Such decisions related to political and military activity, religious matters and territorial occupation. The Gurmata and the Sarbat-Khalsa were the obverse and the reverse of the same political coin. When the forces (misls) of several leaders voluntarily combined for joint action under the overall command of one of themselves it was called the Dal-Khalsa. The successive invasions of Abdali account for the frequency of joint action, often under Jassa Singh Ahluwalia. The decision to establish protective influence was known as Rakhi, denoting an offer of protection to a village or villages against the claimants of land revenue, subject to the payment of much lighter revenue to the Khalsa. Often the area coming under the Rakhi of an individual Singh later came under his regular occupation, and the other members of the Khalsa respected his prior claim over such an area. Bute Shah, a near contemporary historian, says that the Rakhi of a sardar of ten horsemen was respected by the sardar of five hundred. The underpinnings of the principle of equality were evident in the working of the Sarbat-Khalsa, the Gurmata, the Dal-Khalsa, and the Rakhi which, together, covered different aspects of a state of war up to the point of regular territorial occupation.43

Collective conquest did not mean collective rule. Even after a conjoint conquest, the territory was parceled out not only among the leaders, but also among their associates down to the individual horseman. In recognition of the leader’s prowess and role, his share was accepted to be much larger. Joint conquests and partitioning of villages, administrative units, towns and cities went side by side. Lahore and Qasur were partitioned in this manner and Amritsar came to have a dozen katras (quarters) belonging to different sardars, each administering his katra independently of others. Let alone the leader, even a partner-in-conquest (pattidar) could exercise full authority in the territory falling in his share, thus realizing the belief that every horseman was destined to be sovereign (hanne hanne hon mir).44

From Fragmentation to Unification and Expansion

According to Bhangu, the actual course of territorial occupation appears to have been regulated initially by a Gurmata passed at the Akal Takht which recognized an individual’s right to keep, administer and bequeath the territory first acquired by him, even if it happened to be a village or two. Most of the enterprising warriors appear to have begun by establishing their sway over their ancestral villages and the neighboring areas. The initial conquests would not stop at the proclamation of sovereignty in 1765. The underlying idea of equality would logically encourage the more enterprising among them to extend their possessions at the expense of their neighbors. As a result, the individual territorial possessions came to vary from a few villages to three to four parganas. For a few years in the 1770s even the ‘province of Multan’ was held by the Bhangi sardar of Amritsar.

There was a corresponding range also in the relative financial and military resources of the emergent rulers. According to the historian Ahmad Shah of Batala, there were four or five hundred sardars in full possession of their territories, but only some of them were prominent,45 presumably with the initial advantages of leadership, military resources, and larger share of territories. Among such sardars, Jassa Singh Ahluwalia set up his headquarters at Kapurthala, Ganda Singh Bhangi at Amritsar, Jai Singh Kanhiya at Batala, Jassa Singh Ramgarhia at Sri Hargobindpur, Gujjar Singh Bhangi at Gujrat, and Charhat Singh Sukarchakia at Gujranwala. Their possessions are estimated to have yielded seven to thirteen lakhs of rupees annually, and they could muster about 5,000 to 10,000 horsemen each. Then there were several sardars of lesser consequence like Nawab Kapur Singh’s nephew Khushal Singh Faizullapuria at Jalandhar, Baghel Singh Karora Singhia at Hoshiarpur, Tara Singh Dallewalia at Rahon, and Milkha Singh Thehpuria at Rawalpindi. Each emergent ruler exercised autonomy within his territories and tried to augment his resources at the cost of his neighbors and even the past partners. By now it is well established that the stereotype of twelve misls or the ‘misldari system’ carries ‘little meaning for Sikh polity during the late eighteenth century.’46

The individual effort and initiative was at full play in the tussle for aggrandizement and supremacy that is reported to have started between Charhat Singh Sukarchakia and Hari Singh Bhangi even before the proclamation of sovereignty in 1765.47 In the absence later on of serious external threat from Kabul or Delhi, the struggle for ascendancy would be as logical as the joint conquest and partitioning of territories earlier. Since the resources of the prominent sardars were broadly at par they had to seek allies. The pattern of alignments and rivalries was inversely related to the pattern of joint conquests. The continual encroachments on the contiguous territories now accounted for the one-time allies or neighbors being ranged on opposite sides: the Kanhiyas fought with the Ramgarhias; the latter were the inveterate enemies of the Ahluwalias; while the Sukarchakias remained the rivals of the Bhangis. In this tussle, the contenders often sought support from the distantly placed sardars and their own misldars or past partners. The latter joined on a voluntary basis, even switching sides in the middle of a conflict.48 By the 1790s, death had removed from the scene nearly all the veterans, except Jassa Singh Ramgarhia, and also some promising second-generation rulers like Gurbakhsh Singh Kanhiya and Mahan Singh Sukarchakia. A fresh spurt of the Afghan invasions enabled the latter’s son Ranjit Singh to occupy Lahore in 1799 that brought him on to the center-stage of regional politics.

Within a decade, Ranjit Singh succeeded in unifying the disparate centers of power created by the Sikhs. He ousted the Bhangi rulers of Amritsar and Gujrat and neutralized the Ramgarhias with support from the Kanhiyas and Ahluwalias. By 1810, all the small and big sardars to the north of the Sutlej felt obliged to either submit to him as vassals or enter his service as jagirdars or be content with subsistence jagirs. Sada Kaur Kanhiya and Fateh Singh Ahluwalia, his allies of many conquests, too became virtually subordinate to Ranjit Singh, in due course losing their territories in the Bari doab to him. His attempts during 1806-8 at the subjugation of the Sutlej-Jamuna divide, particularly the major Sikh principalities of Patiala, Nabha and Jind, were thwarted by the British who had recently conquered Delhi. They obliged him to enter into a ‘treaty of friendship’ with them at Amritsar in 1809. The Sutlej became the southern boundary of Ranjit Singh’s territories, but he could expand in other directions. By 1819 Ranjit Singh had subverted the non-Sikh rulers of the plains and hills and wrested Attock, Multan and Kashmir from the Afghans. He established suzerainty over Peshawar and the trans-Indus areas in the early 1820s and annexed these in the next decade. Stretching across the plains and hills of north-western India, Ranjit Singh’s state had the dimensions of an empire.

As the sole surviving sovereign ruler in the Indian subcontinent, Ranjit Singh could keep the British imperialism at bay by his diplomatic initiatives and restraint. While he jealously upheld and preserved his sovereignty, Ranjit Singh earned the respect of the British for his sagacity and military power. After his death in 1839 came in quick succession four rulers and four prime ministers. Death and intrigue came in the way of the effective administration of the state of Lahore, or maintenance of friendly relations with the British. After the Khalsa army lost to the British in early 1846 the state of Ranjit Singh became subject to them, to be truncated and eventually annexed to their empire in March 1849.

The Rule of the Khalsa

The rule of the Khalsa began formally in 1765 with the declaration of sovereignty. However, the much larger scale and greater complexity of Ranjit Singh’s dominions introduced a qualitative difference between him and his predecessors, or between his own earlier and later career as a ruler. Yet, in terms of the state policies and ethos, there was a difference mainly of degree between Ranjit Singh and the early Khalsa rulers. A broad continuity of policies and measures can be discerned particularly in the upper doabs between the rivers Sutlej and the Chenab. This area remained under sovereign Khalsa rule for the longest period – from 1765 to 1845 – and constituted the core region of the Khalsa dominions.

In the process of creating the new centers of power the early conquerors soon approximated to the monarchical form, the only system known to them. The idea of equality did not find any democratic expression for the government and administration of the Sikh rulers. Even the ideal state visualized in the contemporary literature happened to be a monarchy. The Sikh rulers looked upon themselves as successors of the Mughals. The earliest available administrative order of an emergent ruler going back to 1752 is emphatic that ‘the established practice’ should not be disturbed.49Conformity with the Mughal structure and personnel became increasingly marked with the passage of time. The administrative apparatus under both the regimes was geared essentially to the interconnected functions of the collection of revenues, administration of justice, and maintenance of law and order, often with military power and an efficient system of intelligence. The charitable grants of revenue were the mode through which the state shared a part of its income with a section of its subjects. Whatever the ultimate source of authority, the rulers exercised de facto power within their own territories and political control over their vassals. The degree of approximation to the Mughal politico-administrative organization has been discussed elsewhere.50 Here we may turn to the bearing of the Khalsa ideology on deviations from the established practices and ethos of medieval Indian polity. In the first place, the Khalsa ideology offered hopes of a better order (satjug), in place of the existing order that appeared to be unjust and oppressive. The contemporary writings envisaged a sovereign state in which power was exercised on behalf of God and the Gurus. Free from oppression and high-handedness, this state offered protection and opportunity to all, including the lowcastes. In the early Rahitnamas, protection of the peasantry and the life and property of all the subjects, and care of the poor and the needy, figure among the ruler’s foremost duties. While state patronage was to be extended to a cross section of the subjects, the ruler was particularly enjoined upon to be considerate towards his fellow Sikhs, irrespective of their means or birth. Above all, the administration of justice figures as the first duty of the ruler in much of the Sikh literature from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, which could be construed as the raison de etre for the political struggle of the Sikhs. That even the ruler was accountable for his conduct figures in the Prem Sumarag as well as the actual orders of Ranjit Singh.51 Furthermore, the available orders of the emergent rulers underline that it was the moral obligation of the ruler (dharm-i Khalsa Jio) to honor an earlier commitment – as much his own as that of his predecessors. In the policies and measures of the state there was to be no discrimination on grounds of religion. The admonitory orders of Ranjit Singh and his predecessors underline their anxiety to protect the ordinary subjects and the men of piety against the high-handedness of the administrators, jagirdars, zamindars and soldiers.52 The tone and content of these orders suggest that not only the early rulers, but Ranjit Singh also was consciously trying to exercise power with moderation and mildness, which could be seen as a version of the halemi raj (from the Persian halimi or mild) conceived by Guru Arjan.53

The new rulers regarded sovereignty as a gift rather than a right. As evident from their coins, they attributed their victory to the Gurus and ultimately to the grace of God. Since their sovereignty was not derived from a temporal authority, it could be presumed to have been vested notionally in the collectivity or the Khalsa Panth. Representing the collectivity within his territories the individual ruler, whether Jai Singh Kanhiya or Ranjit Singh, styled himself as the ‘Khalsa Ji,’ or ‘Singh Sahib’; on their seals they used the phrase ‘Akal Sahai,’ God the Helper. In deference to the doctrine of Guru Panth they neither assumed regal titles, nor sat on a throne, nor did they use any elaborate ceremonial at the court. Compared to the weakest of the Mughals in the early eighteenth century, the court (deorhi) of the most powerful of the Sikh rulers a century later was an informal affair.

At the same time, the framework within which the collectivity had been operating, that is the Sarbat-Khalsa, Gurmata and the Dal-Khalsa, had lost its relevance in the new situation. After the occupation of Lahore in 1765, the Sarbat-Khalsa is believed to have been convened only on two or three occasions – in the face of the Afghan efforts to regain the Punjab, and the large militrary presence of the Marathas. But the Sarbat-Khalsa now consisted of the chiefs and it was not followed by any collective decision and action. When the remnants of the eighteenth century warriors, called the Akalis or Nihangs, tried to assert themselves as the self-styled guardians of the Guru Panth, they were tolerated and humored, and even inducted into the political system as a special category of warriors, though as recipients of jagirs and dharmarth like others. Thus, when it came to government and administration, the egalitarian idea of the Guru Panth unobtrusively yielded place to the idea of the Guru Granth which circumscribed equality to the sacred space.

After the establishment of Khalsa rule, the Gurdwara or the erstwhile dharmsal occupied important place in the life of the fraternity of believers. Several new Gurdwaras associated with the Gurus and the well-known martyrs came up, with the Granth installed therein for worship. The individual ruler paid obeisance to the Granth, listened to it daily, sitting on the floor and as a member of the community of believers. Equality before the Granth as the Guru and patronage of Gurdwaras reinforced his position as the source of de facto power. While deference was shown to the principle of equality within the Gurdwara, the life outside its precincts recognized the inequalities in power, wealth and status arisen in the course of acquisition of power under the Khalsa Rule. Revenues were assigned for the Harmandir Sahib and other Gurdwaras by the Sikh rulers and their jagirdars as the most common expression of piety. The centrality of the Harmandir Sahib was reinforced in the 1770s when it was collectively rebuilt finally by the new rulers under the overall supervision of Jassa Singh Ahluwalia.54 Its gold-plating by Ranjit Singh was an eloquent expression as much of his devotion to this central shrine of the Sikhs as of his pre-eminent position among them.

Accommodation to the existing foci of power in the region, both Sikh and non-Sikh, was a characteristic feature of the new political order. Like his predecessors, Ranjit Singh allowed the descendants of the erstwhile partners-in-conquest (pattidars), sometimes even their widows or daughters, to continue holding their villages on terms of paying a token tribute (nazrana) and furnishing horsemen. The descendants of the misldars or leaders of bands of horsemen were generally allowed to remain in autonomous possession of their territories on terms of maintaining contingents. In the process of reducing the Sikh rulers to subordination, military support and the payment of nazrana were generally asked for. In their case, Ranjit Singh appears not to have insisted upon all the Mughal conditions of vassalage. Rather, he showed so much of consideration towards them that the sovereign rulers almost unobtrusively passed into vassalage or subordination. The Rajput hill chiefs and the Pathans, however, were formally required to station their representatives at the court of Ranjit Singh, and succession to their position was approved only on the payment of tribute.

Dispossession was a necessary condition of state formation, but in consonance with the dictum that ‘none should remain a foe or stranger,’55the dispossessed rulers were conciliated and accommodated by offers of service. If they did not wish to serve the new state, they could still subsist on jagirs given for their maintenance. There is no known instance of a dispossessed ruler or his jagirdar under the Khalsa Raj who was not offered accommodation in this manner. When Ranjit Singh annexed the territories of Sahib Singh Bhangi, his staunch rival and also of his father’s, he allowed a pargana to remain with Sahib Singh for his subsistence. Similar consideration was shown to the dispossessed non-Sikh chiefs by the early Sikh rulers in the upper doabs and by Ranjit Singh in the hills and the plains outside the core region too. The subsistence jagirs, however, were gradually reduced or resumed with the passage of time, and certainly after the death of the incumbent. The local leaders in the tribal territories in the Chaj doab were similarly reconciled to the new rule through the grant of one-fourth share of the revenues (chaharam) of their localities. The process of downward mobility was seldom sharp in the political process outlined above.56

The administration of land revenue appears to have been informed as much by the Khalsa ideology outlined above as by the close equation between the Khalsa and the peasant during the period of political struggle. Through the lesser rates of revenue collected under the Rakhi in the 1750s the emergent conquerors had already offered hopes of a set-up more accommodating to the peasant. The contemporary European observers notice their concern for the safety of crops and protection of cultivators. After the new rulers stabilized their position, concern for the peasantry became the corner stone of their administration. In place of the fixed cash assessment based on measurement (zabt), which had been prevalent under the Mughals and which needed more elaborate machinery and fell more heavily on the producer, the cultivator was allowed to opt for crop-sharing (batai) and appraisement of the standing crop (kankut). The larger incidence of payments in kind in the early years also was more favorable to the peasant. When the state share was commuted into cash under Ranjit Singh, the conversion rate was determined according to the prices current, but with the concurrence of the village headmen and the peasant proprietors. The built-in flexibility in batai, kankut and payments in kind enabled the cultivator to adjust better with the vagaries of weather. In the event of natural calamities the state gave remissions and allowed accumulation of the arrears of revenue rather than oblige the cultivator to flee in desperation.

Extension of cultivation and the founding of new villages became an important feature during the last quarter of the eighteenth century and the first quarter of the nineteenth. The early British administrators testify that the Bist Jalandhar doab, ‘a perfect wilderness’ only about a century ago, turned into the ‘Garden of the Punjab.’57 Large areas in the upper Bari, Rachna and Chaj doabs were brought under cultivation by reclamation of waste lands, grant of taqavi loans, digging or reopening of wells, excavation of canals, and concessional rates of revenues and other incentives to the colonizers. Extension of cultivation and the replacement of deserters figure prominently in Ranjit Singh’s standard instructions to the administrators and revenue-collectors. The pastoral tribes were encouraged to settle down to agriculture. Many ‘Sikh’ villages came up in the core region as a result of the encouragement given to the industrious tenants (mostly Jats) to oust indolent proprietors. The tenants acquired hereditary rights in the land brought under cultivation with their labor and the landlord had to be content with small proprietary dues. This leveling process functioned in favor of the working rural population. The village artisans often pursued agriculture along with their traditional occupations, at places cultivating land even as co-sharing proprietors. Dislodging of the actual cultivators by the revenue administrators, zamindars and moneylenders was frowned upon by the rulers. Thus, the extension of cultivation in the upper doabs and upward mobility among the lower rungs of agrarian society went side by side.

As may be expected a priori, there was a close correspondence between the Khalsa ideology and the administration of justice in the Khalsa dominions. In an order of 1825 Ranjit Singh instructed his administrators of Lahore ‘to dispense justice in accordance with legitimate right and without the slightest oppression..… to pass orders in consultation with the Panches and Judges of the city, and in accordance with the Shastras and the Quran, as pertinent to the faith of the parties.’ The order of 1831 further instructed the administrators:

You should not permit forcible possession to be taken of any person’s land or any person’s house to be demolished. Nor should you allow any high-handedness to be practised upon woodcutters, fodder-vendors, oil-vendors, horse-shoers, [manu] factory-owners etc. …. You should prevent the oppressor from oppression. You (…) should not permit anybody to be treated harshly [italics ours].

The addressees are further instructed to obtain through regular channels, ‘news of all happenings so that every person’s rights are secured and no person is oppressed.’58 On this conception of justice hinged the effective governance of the state under Khalsa rule.

Wherever in operation, the existing agencies of justice were retained and recognized – the qazi’s courts, the muhalla panchayats in towns, and the committees of elders in villages. The early British administrators testify to the efficacy and credibility of the village panchayats. In addition, the ruler himself administered justice and, depending upon the size of his territories, entrusted this responsibility to others. With the unification of Sikh territories under Ranjit Singh, the agencies of justice came to include the provincial governors (nazims), pargana or ta′alluqa administrators (kardars), and the large jagirdars. Ranjit Singh also appointed the ‘adaltis’ or mobile justices who in all probability functioned in the rural areas of the core region. The available legal documents suggest that in matters of property transactions non-Muslims also resorted to the qazi’s court. A striking aspect of the administration of justice was the leniency of punishments. Murders and even cases of gross insubordination in the army were punished with fines, deductions in salary, and demotions. In case of a Purbia soldier convicted of murder, Ranjit Singh ordered him to be exiled across the Sutlej, with his face blackened. Even in case of the attempted assassination of Ranjit Singh himself, the culprit was allowed to get away with his life. In deference to the Khalsa ideology, rather than to tribal customs in some peasant societies, capital punishment was virtually non-existent as an accepted feature of the judicial system under Ranjit Singh and his Sikh predecessors.59

In accordance with the principle of freedom of conscience, and the norm of state patronage covering all faiths, the new rulers took the age-old institution of religious charity and revenue grants (madad-i ma′ash) to a new height, perhaps nowhere else reached in India. They scrupulously confirmed the existing charitable grants being enjoyed by every mosque, khanqah, takia, temple, dera and gaddi. In one of his orders an early ruler explicitly states: ‘Few have known this truth that by the grace of the True Guru, there is no discrimination.’60 The orders of several other rulers and, later Ranjit Singh, echo this sentiment. Evidently, the quarrel of the Khalsa had been with the then state, metaphorically the ‘Khans’ or the ‘Turks,’ but not necessarily with the faith of its rulers and the majority of its functionaries. Therefore, as they settled down, the Khalsa rulers also gave fresh grants to Islamic places of worship and men of piety. Understandably, a large number of temples, Vaishnav and Jogi establishments, cowsheds and Brahmans received fresh grants by way of religious charity, generally called dharmarth under the core areas of the dominions of Ranjit Singh.

When it came to the individuals and institutions in Sikhism, the rulers’ munificence knew no bounds. In addition to the generous offerings of revenue made to the Harmandir Sahib and other Gurdwaras, the largest amount of revenues went to the Sodhi and Bedi descendants of Guru Ram Das and Guru Nanak. The Udasis, who traced their lineage to the elder son of Guru Nanak and had their own akharas, and who had become the custodians of most of the Gurdwaras during the period of political struggle, were the largest single group amongst the recipients of state patronage by the time of Ranjit Singh. Compared to the proportion of the total revenues alienated by Akbar in the upper doabs as madad-i ma′ash, the proportion of the total revenues given away as dharmarth under Ranjit Singh was nearly four times. Significantly, these extensive revenue grants to the Sikh institutions and individuals had been given at the cost of the state, and not of other faiths. The dharmarth grants may be seen as an expression of thanks-giving for the gift of rulership and a way of sharing the benefits of the newly acquired power with one’s coreligionists who had not been in receipt of state patronage earlier. Moreover, through these grants the orthodoxy in general and the descendants of the Gurus in particular, were harnessed in support of the political order as custodians of shrines, as warriors, and as mediators between contending parties. Their moral authority notwithstanding, they remained subject to the political authority of the ruler who arbitrated in their disputes over succession and distribution of offerings. Cumulatively, the charitable grants were an expression of a sense of piety as well as catholicity built into the Khalsa ideology. Yet, it would be unrealistic to assume that the recipients of charities did not become the votaries of the new regime.

Composite Ruling Class and the ‘Khalsa’ Army

The catholicity and openness built into the Khalsa ideology helped to broaden the state’s base and encourage individual initiative and enterprise based on the idea of equality. Therefore, the new rulers did not have to draw only upon their coreligionists as the props of power.

Ranjit Singh tapped the expertise and talent available within the region, sharing in the process, power and resources of the state with different sections of population in his dominions. For collecting revenues, maintaining accounts and treasuries, and running the civil and military establishments he largely depended upon the Khatris, Aroras, and Brahmans from the upper doabs who had traditionally been associated with civil administration at the intermediate levels. With the expansion of his territories in the hills, Ranjit Singh increasingly inducted the Rajputs into the army; the Dogras of Jammu came to enjoy important positions in the state by the early 1820s. The Sayyads and Pathans from the core region had been associated with civil administration and army since the early years. Ranjit Singh’s court attracted talent also from the Ganga-Jamuna Doab and Kabul. Some Europeans too joined his service. These non-Sikh members of the new ruling class came to hold positions at the primary level of the power structure – as ministers, diwans, treasurers, provincial governors, and commanding officers in the army. They were mostly paid through jagirs. Majority of them happened to be Khatris and Brahmans from the core area of the Khalsa Raj. They appear to have improved their position considerably in the new regime.

The maximum social mobility was evident in the case of the Sikhs. The Sikh members of the new ruling class happened to be from amongst the Jats, distantly followed by some Sikhs from the Khatri, Brahman, Tarkhan (carpenter), Kalal (distiller), Nai (barber) and the low-caste (Mazhabi) backgrounds. Their jagirs ranged from Rs. 25,000 to over Rs 800,000 a year. Hari Singh Nalwa was the biggest recipient of revenues in the 1830s. Following the Mughal practice, the members of the established Sikh families came to be referred to as the ‘qadim khanazads.‘61 At the same time, the Khalsa ethos of equality and enterprise and aspiration to rule often asserted itself, even threatening Ranjit Singh’s pre-eminence and sometimes also his person. Therefore, Ranjit Singh appears to have tried to depress the Sikh ruling class in relation to himself. The erstwhile Sikh rulers and their jagirdars who had reluctantly accepted his vassalage or service were neutralized by the elevation of his own collaterals, companions, troopers and servants (khidmatgars) to positions of eminence as ‘sardars’ and jagirdars. The well-known families of the Sandhanwalia and Majithia ‘sardars’ and Hari Singh Nalwa were amongst them. Towards the end of Ranjit Singh’s reign, the majority of his ‘principal’ nobles classified in the Khalsa Darbar Records as the ‘sardaran-i-namdar’ and the ‘sardaran-i-kalan’62 were his creatures.

By the early 1830s, Ranjit Singh’s hegemony over his ruling class was fairly well established. He decreased or transferred their jagirs at will, regulated their audience and departure, inspected their forces, audited their accounts, punished their lapses, settled their disputes, and received gun salutes and extracted nazrana from them on all possible occasions. Whether his sons, or the collaterals, or the sardars, or the vassals, or the descendants of the Gurus – no one was outside the purview of Ranjit Singh’s authority and discipline. This is not to say that he had no problems in ensuring compliance of his orders by the Sikh Jats among his ‘principal’ sardars. There are indications that in the last decade of his rule, he was promoting more non-Jats and non-Sikhs to the highest positions. According to Sohan Lal Suri, his court chronicler, Ranjit Singh persuaded Khatris to take the Sikh baptism (pahul), with jagirs and promotions as incentives. Tej Singh, a born Brahman hailing from the Ganga-Jamuna Doab, who had taken the Sikh baptism was the officer commanding of the standing army (kampu-i mu′alla) during the Peshawar campaign of 1834-35. He was made a ‘General’ in 1835. Of the seven other officers promoted along with him more than half happened to be non-Sikhs. In 1837 high-sounding titles were bestowed upon the Sikh and non-Sikh members of the ruling class. Their disputes were settled in the presence of Raja Dhian Singh, the Dogra, who was virtually being treated as the prime minister. In 1827 Ranjit Singh had conferred the title of raja-i-rajgan raja kalan bahadur upon Dhian Singh.

As a logical corollary of these developments, the golden plaque on the main door of the Golden Temple, which was inscribed in 1830, formally used the title ‘Maharaja’ for Ranjit Singh.63 For long he had allowed himself to be addressed as the ‘Maharaja’;64 his orders had referred to him by the exalted titles like ‘Huzur-i Anwar’, ‘Sarkar-i Ali’ and ‘Sarkar-i-Wala.’65 The treaties with the British signed in the 1830s now clearly used the title Maharaja for him.66 The gun ‘Ram Ban’ especially inscribed for him during this decade calls him ‘Maharaja-Dhiraj.’67 Significantly, the ideal of monarchy had not been distant earlier also when several of his Sikh predecessors came to be referred to as ‘Sarkar,’ ‘Sarkar Khalsa Ji,’ and ‘Patshah’ – by the contemporary and near contemporary writers.68

As evident from his orders of 1833-35, Ranjit Singh turned the festivals of Dussehra, Basant and Holi into state functions celebrated with éclat, deriving great psychological advantage for his position, and that of the heir-apparent. The troops wore uniforms dyed in yellow for inspection by Kanwar Kharak Singh. For the Holi celebrations, each unit in the standing army was issued colored powder (alta) and then given three days leave for washing the uniforms. For the Dussehra celebrations of 1835 the Maharaja got a ceremonial pavilion especially prepared for audience; promoted the officers in the army and administration; gave them robes of honor and other gifts; and specified the number of caparisoned horses, camels and gold pieces (butkis) to be offered by each one of them as the nazr. On this occasion some units received new flags and the rest received money for the worship (puja) of their standards. Ceremonial volley-firing (shalak-salami) by 30,000 troops at the rate of twenty-one cartridges per person was a feature of the occasion.69 The form and scale of these celebrations put Ranjit Singh at the center of the two wings of his power – the ruling class and the army.

Ranjit Singh’s reorganization of the army and his keen personal interest in its recruitment, training and discipline along Western lines are well-known.70 Besides staying in cantonments and getting cash salaries, the Westernized sections of the army came to have a regular hierarchy of officers and non-combatants, training and drills, uniforms and inspections, and messing and supply system. The Western features appear to have harmonized well with the Khalsa tradition and heightened the corporate identity of the army. In addition, Granthis were appointed on the regular staff of each unit, while the Granth was deposited near the flag that denoted the headquarters of the unit.

By the 1830s, the Sikhs constituted 50 per cent of the men and officers in the artillery, and dominated all other wings of the army. Ranjit Singh’s orders to military commanders show that without slackening discipline, he evinced a keen interest in the welfare of the troops and advised the officers to keep them in good humor. As a result of his promptness to reward the meritorious with promotions and other incentives, a trooper could become an officer and even rise to be a commander within a few years of joining his service. In Ranjit Singh’s military organization, soldiers and officers were punished generally through fines, deductions and demotions, and rarely through dismissals. Ranjit Singh not only created the best regulated indigenous army,71 he was also able to nurture in the army a sense of identification with himself, with his state, and with the Khalsa Panth.72

In this background it is not surprising that the quick changes of rulers and prime ministers after Ranjit Singh had an adverse effect on the army and its discipline. To contain and use this army, the rulers and ministers doubled its pay and strength. The largest increase, understandably, was in the ranks of the irregular cavalry. Despite the induction of the Rajputs and Pathans as a counterpoise against the Sikhs, they continued to constitute the overall majority; there was hardly any unit without them. After the assassination of Maharaja Sher Singh and Raja Dhian Singh in 1843, the army assumed a political role, presumably invoking the doctrine of Guru Panth. The elected panchayats or regimental committees sprang up to revive the collective functioning of the days of the political struggle against the Mughals and Afghans. The panchayats issued directives to the ruling family, the Prime Minister and their own commanders in the name of the ‘Panth Khalsa Ji.’ The officers were divested of all disciplinary powers. In due course, each company elected two chaudharis who were reported to have imposed a strict discipline over the troops.73 It may be safely assumed that even the non-Sikh troops raised by Ranjit Singh were with the Khalsa when it came to a threat to one of his sons or to the stability of the state. Colonel Richmond, the British Political Agent posted across the Sutlej at Ludhiana, observed in 1844 that,

The Sikhs are still imbued with much of the enthusiasm of the reformers and with much of the activity of mind and resolution of purpose…. They will still dare and endure much for the Khalsa.74

The high morale of the Khalsa army was in marked contrast with the anxiety and demoralization of the ruling class. Ranjit Singh’s generosity, and the wealth accumulated over the past two or three generations, appear to have weakened the resolve of several of them to either risk controlling the army or try directing the political affairs. Those officers who had the most to lose in power and privileges sought to preserve these by hobnobbing with the British who at any rate had been seriously debating the issue of conquest of the Punjab after the occupation of Sindh in 1843. Encouraged but unsupported by the ruling class, and provoked by the British, the army crossed the Sutlej in the name of the Khalsa Panth and in defense of the sovereignty of the Khalsa.

Ideology and Praxis in Restrospect

The popular decision to go to war with the British and continuation of the Nanak Shahi coins into the 1840s symbolically wrap up the period from the institution of the Khalsa by Guru Gobind Singh to the end of the Khalsa Raj. While the ideal of sovereign rule remained in the backdrop all through, all the elements in the Khalsa ideology were not equally operative between these two points of time. The bearing of the ideas of equality and social commitment with willingness to die for a cause was pronounced in the course of political struggle. The idea of equality underpinning the doctrine of Guru Panth provided a framework for collective action in the course of warfare and initial conquests.

In the tussle for autonomy and ascendancy, however, the doctrine of Guru Granth came to the fore, providing for equality before the Granth and in the Gurdwara. The principle of equality continued to encourage the persons of ability and promise to aspire to reach the highest military and civil positions in the state. Catholicity built into the Khalsa worldview enabled non-Sikhs to participate in the state at all levels of the power structure. The ideal of freedom of conscience found a powerful expression in the extension of state patronage to all faiths. Simultaneously, the leading Sikh shrines and the descendants of the Gurus were won over by generous revenue-grants by the new rulers. The ideal of freedom from oppression got translated into the markedly pro-peasant policies of the new rulers. Finally, the concept of halemi raj appears to have come out in the sharpest relief in the administration of justice. Together, the different elements in the Khalsa ideology appear to have legitimized the Khalsa Raj in the eyes of its non-Sikh subjects who greatly outnumbered the Sikhs.

It is axiomatic that there would be tension between the ideology and praxis in this complex and protracted political process. Even when Ranjit Singh and his Sikh predecessors were akin to the Khalsa warriors of the pre-territorial days in subscribing to the religious ideology, the new rulers also looked upon themselves as monarchs who jealously upheld their sovereignty. While they tried to administer with consent and accommodation, military power remained their mainstay. Yet, this most powerful polity created in the Punjab in its entire history, was administered with much less force and bloodshed compared to any other state in medieval India. The Sikh as well as non-Sikh subjects of the Khalsa Raj in its core areas came to identify themselves with the new political order as much because of its extensive patronage, as for providing equality of opportunity both normatively and effectively. Its epitaph was written in Punjabi by a Muslim poet: Shah Muhammad.75

Notes

[Editorial Note: This paper is a substantially revised version of the author’s earlier publications on the theme. For an overview of the period, the reader may refer to the author’s Agrarian System of the Sikhs: Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century (New Delhi: Manohar, 1978), but as a whole, the present paper complements the Agrarian System.]

1. For a discussion of such contradictory characterizations, J.S. Grewal, Sikh Ideology, Polity and Social Order: From Guru Nanak to Maharaja Ranjit Singh (New Delhi: Manohar, 2007, 3rd [rev. edn.]), pp. 162-63.

2. For the essential elements in the Khalsa ideology, idem, The Sikhs of the Punjab, The New Cambridge History of India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 28-81. For a definition of ideology, L.B. Brown, Ideology (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973), pp. 9-10, 173.

3. This understanding is based on those manuals of right belief and conduct that are now believed to have been compiled during the life time of Guru Gobind Singh or soon thereafter, notably the manuals attributed to Bhai Nandlal, Chaupa Singh (in part), Prahlad Singh, Daya Singh, and the anonymous work generally called the Prem Sumarag. For their texts, see Rahitname (Punjabi), ed., Piara Singh Padam (Amritsar: Bhai Chattar Singh-Jiwan Singh, 1991 [1974]), pp. 54-133. I am grateful to Professor J.S. Grewal for lending his forthcoming articles on the Chaupa Singh Rahitnama, Sakhi Rahit Ki, and the Prem Sumarag.

4. Karamjit K. Malhotra, ‘The Earliest Manual on the Sikh Way of Life,’ in Reeta Grewal and Sheena Pall, eds., Five Centuries of Sikh Tradition: Ideology, Soceity, Politics and Culture (New Delhi: Manohar, 2005), pp. 70-71, 75-76. Cf. W.H. McLeod, Sikhs of the Khalsa: A History of the Khalsa Rahit (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2003), pp. 82-87; idem, Prem Sumarag: The Testimony of a Sanatan Sikh (New Delhi: OUP, 2006), pp. 1-9.

5. Sainapat, Shri Guru Sobha (Punjabi), ed., Shamsher Singh Ashok (Amritsar: Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee, 1967), p. 132.

6. For a contemporary bardic account of Banda Singh’s meeting with Guru Gobind Singh, see Amarnama (Punjabi), ed. Ganda Singh (Amristar: Sikh History Society, 1953), pp. 26, 46. For detail, Ganda Singh, Life of Banda Singh Bahadur (Patiala: Punjabi University, 1990 [1935]), pp. 10-22.

7. Grewal, Sikh Ideology, Polity and Social Order, pp. 96-106.

8. According to a contemporary Persian account, Batala and Kalanaur in the upper Bari doab, some tracts in the upper Rachna doab, and even the city of Lahore were affected by the spontaneous uprisings of the Sikhs. Muhammad Qasim ‘Ibrat,’ Ibratnama, tr. Irfan Habib, in J.S. Grewal and Irfan Habib, eds., Sikh History from Persian Sources (New Delhi: Tulika/Indian History Congress [cited hereafter as SHPS]), pp. 118-20.

9. For a description of these coins, see Surinder Singh, Sikh Coinage: Symbol of Sikh Sovereignty (New Delhi: Manohar, 2004), p. 41. For a contemporary statement of the areas coming under Banda Singh’s control, see Mirza Muhammad, Ibratnama, tr. Iqbal Husain, in SHPS, p. 135.

10. For facsimiles of the orders of Banda Singh using this seal, see Ganda Singh, ed., Hukamname (Patiala: Punjabi University 1967), nos. 66 and 67, pp. 192, 194.

11. Ibid., 67, pp. 194-95.

12. Shri Guru Sobha, pp. 136-38.

13. The contemporary Mirza Muhammad marvels at the demeanor of Banda’s men, with ‘no sign of humility and submission on their faces.’ Rather, when they were being paraded through the city riding on the camels’ backs, they ‘kept singing and reciting melodious verses.’ Ibratnama, in SHPS, p. 140. An ‘English Report of Banda Bahadur’s Arrival as Captive at Delhi,’ dated 10 March 1716, says that while a hundred of his companions are beheaded each day, ‘it is not a little remarkable with what patience they undergo their fate, and to the last it has not been found that one apostatized from this new formed Religion.’ Quoted in SHPS, p. 127.

14. Prachin Panth Prakash (Punjabi), ed., Bhai Vir Singh (New Delhi: Bhai Vir Singh Sahit Sadan, 1993[1914]), pp. 131-33.

15. , pp. 210-13.

16. , pp. 214-16.

17. Gurinder Singh Mann, ‘Sikh Educational Heritage,’ Journal of Punjab Studies, 12, no. 1 (Spring 2005), p. 12.

18. This was reported by Muhammad Qasim ‘Ibrat’, SHPS, p. 118.

19. Bhangu, Prachin Panth Prakash, pp. 222-27. See also, Gurtej Singh, ‘Bhai Mani Singh in Historical Perspective,’ Proceedings Punjab History Conference (Patiala: Punjabi University, 1968), pp. 122-24, n. 21.

20. Ahmad Shah Batalia, Tarikh-i Hind (Persian), MS 1291, Sikh History Research Department, Khalsa College, Amritsar [cited hereafter as SHR], p. 315.

21. Mufti Aliuddin, Ibratnama (Persian), MS SHR 1277, pp. 284-85. See also, Hari Ram Gupta, History of the Sikhs, vol. I: 1739-68 (Simla: Minerva Bookshop, 1952 [1939]), pp. 49-50n.

22. N. Goswamy and J.S. Grewal, The Mughal and Sikh Rulers and the Vaishnavas of Pindori: A Historical Interpretation of 52 Persian Documents (Simla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study, 1969), documents XVIII, XIX, XXIV and XXV, pp. 205-11, 227-33.

23. According to a news-report of October 1760 from Delhi, having ‘established their tax collection’ in the province of Lahore as well as the Jalandhar doab, the Sikhs were sharing the country ‘with the Shah.’ SHPS, p. 189.

The news-reports included in this collection pertain to the period from 1759 to 1765 and were probably meant for the Nizam of Hyderabad, according to the translator, Professor Irfan Habib, who finds the reports as ‘fairly creditworthy.’

24. In ibid., p. 181.

25. Bhangu, Prachin Panth Prakash 368.

26. SHPS, p. 190.

27. , p. 195.

28. This graphic description given by Bute Shah, and reiterated by Cunningham, is suggestive of the general process of territorial occupation by the Khalsa. Bute Shah, Tarikh-i Panjab (Persian), MS SHR 1288, p. 458; Joseph Davy Cunningham, A History of the Sikhs, ed. H.L.O. Garrett (New Delhi: S. Chand, 1994 [1849]), pp. 92-93.

29. SHPS, pp. 195-97, 200. This particular engagement in which the Afghan army was completely routed and Ahmad Shah’s personal baggage was ‘put to sack,’ does not find mention in the earlier studies of the period, including my own.

30. , p. 199.

31. Jangnama (Persian), MS SHR 1547, p. 177.

32. SHPS, pp. 190-91, 192, 193, 195, 196, 199.

33. , p. 194.

34. Jangnama, tr. Iqtidar Alam Khan, in ibid., p. 207.

35. Bhangu, Prachin Panth Prakash, pp. 414-25. The Khalsa constructed a shahidganj or place of worship where Nihang Gurbaksh Singh and his martyr companions were cremated at Amritsar.

Significantly, in this context, Ratan Singh Bhangu expounds his own philosophy of martyrdom with three interrelated features: armed struggle, sacrifice of life, and rulership as reward. J.S. Grewal ‘Valorizing the Tradition: Bhangu’s Guru Panth Prakash,’ in J.S. Grewal ed., The Khalsa: Sikh and Non-Sikh Perspectives (New Delhi: Manohar, 2004), pp. 113-16.

36. SHPS, p. 20.

37. For an early account of these coins, C.J. Rodgers, ‘On the Coins of the Sikhs,’ Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (1881), pp. 79-82. Cf. Surinder Singh, Sikh Coinage, pp. 62-63.

38. The individual rulers in the tract to the north of the Sutlej are said to have established mints in the pargana towns in their territories. The issues of the mint at Amritsar being heavier in weight were continued by Ranjit Singh. Ganesh Das, Char Bagh-i Panjab (Persian), ed. Kirpal Singh (Amritsar: Khalsa College, 1965), pp. 132-33. However, the coins of the rulers of Patiala and Jind (not Nabha) acknowledged the overlordship of Ahmad Shah Abdali. Lepel H. Griffin, Minor Phulkian Families (Patiala: Language Department Punjab, 1970 [1870]), pp. 286-88, nn.

39. For a study of the contrast between the Sikh conquerors and the other aspirants for political power from amongst the administrators, jagirdars, zamindars, ijaradars and madad-i-ma′ash grantees who operated within the framework of the Mughal empire, see Veena Sachdeva, Polity and Economy of the Punjab during the Late Eighteenth Century (New Delhi: Manohar, 1993), pp. 16-63. Cf. Muzaffar Alam, The Crisis of Empire in Mughal North India: Awadh and the Punjab (Delhi: OUP, 1986), pp. 176-203.

40. SHPS, pp. 208-9.

41. , p. 209. Cf. Arjan Dass Malik, The Sword of the Khalsa: The Sikh People’s War 1699-1768 (New Delhi: Manohar, 1999 [1975]), pp. 83-94.

42. Rahitname, p. 59; Malhotra, ‘The Earliest Manual on the Sikh Way of Life,’ p. 76.

43. The cohesive devices emerging under the doctrine of Guru-Panth were first conceptualized in these terms by J.S. Grewal, ‘Eighteenth-Century Sikh Polity,’ in From Guru Nanak to Maharaja Ranjit Singh: Essays in Sikh History (Amritsar: Guru Nanak (Dev) University, 1972), pp. 97-99. For elaboration, Banga, Agrarian System, 29-31; Sachdeva, Polity and Economy of the Punjab, pp. 86-91.

44. Bhangu, Prachin Panth Prakash, p. 131.

45. S. Grewal, ‘Ahmad Shah of Batala on the Sikh Misl,’ in Sikh Ideology, Polity and Social Order, p. 149.

46. Sachdeva, Polity and Economy of the Punjab, p. 97.

47. According to a news-report from Delhi, dated 4 April 1764, soon after the rout of Abdali, the men of Hari Singh Bhangi and Charhat Singh, acting independently of one another, tried to take control of Lahore. ‘Two hundred persons from both sides were killed or wounded’ before peace could be arranged between them. Another news-report of 20 May 1764 referred to ‘the differences and fighting among Jassa Singh Kalal [Ahluwalia] and other Sikhs’ in the Jalandhar doab. SHPS, pp. 197, 198.

48. For graphic descriptions of territorial disputes and changing alliances during the last quarter of the eighteenth century, Ram Sukh Rao, Sri Fateh Singh Partap Prabhakar, ed. Joginder Kaur (Patiala: published by the editor, 1980 [cited hereafter as Fateh Singh Partap Prabhakar]), pp. 65, 89, 119, 148, 238 et passim.

49. Goswamy and Grewal, eds., Mughal and Sikh Rulers, document XVIII, pp. 205-6; also, document XXIII, pp. 223-25. In another collection of charitable grants a Sikh ruler emphasizes that ‘deviation from an old practice is not to be commended.’ Idem, The Mughals and the Jogis of Jakhbar: Some Madad-i-Ma′ash and Other Documents (Simla: IIAS, 1967), document XVII, pp. 189-91.

50. See the author’s Agrarian System, particularly pp. 188-93.

51. McLeod, Prem Sumarag, p. 84.

Two extant orders of Ranjit Singh of 1825 and 1831, addressed to Fakir Nuruddin and others as administrators of the city of Lahore, underline that neither the ruler himself, nor his sons, nor the highest among his nobles should be allowed to ‘commit any inappropriate act.’ For the facsimiles and translation of these orders see Fakir Syed Waheeduddin, The Real Ranjit Singh (Karachi: Lion Art Press, 1965), pp. 31-33.

52. This comes out, among others, in a unique collection of orders issued by Ranjit Singh to General Tej Singh as the Officer Commanding of the Standing Army (kampu-i mu′alla). J.S. Grewal and Indu Banga, trs. and eds., Civil and Military Affairs of Maharaja Ranjit Singh: A Study of 450 Orders in Persian (Amritsar: Guru Nanak Dev University, 1987).

53. Guru Granth Sahib, Sri Rag, p. 74:

Through the Will of the Merciful Lord

None is oppressed by another, and everyone lives in comfort.

Thus has been established the rule by mildness.

For a discussion of this concept in a broader context, see J.S. Grewal, ‘Guru Arjan’s Halemi Raj,’ in Lectures on History, Culture and Politics of the Punjab, Vol. II (Patiala: Punjabi University, forthcoming), pp. 1-36.

54. Fateh Singh Partap Prabhakar, p. 40; Madanjit Kaur, The Golden Temple: Past and Present (Amritsar: GNDU, 1983), p. 52. 2-25

55. Grewal, ‘Guru Arjan’s Halemi Raj’, p. 34.